Having lost power for the past couple of days due to Hurricane Irene, I played a lot of the card game Dominion with family.

Dominion is generally considered a "German-style" game, meaning that all players are in until the end, the theme is economic (rather than military, like Stratego or Risk), there is little direct interaction between players, and it requires an intermediate level of strategy (more than Pictionary but less than Chess).

Dominion is one of my favorite tabletop games, and was my first introduction to the German style. I can generally play it for hours and never get bored. If I ever did, Dominion has expansions which add new mechanics to provide flavor to the core experience.

But while Dominion is a near perfect game, it strikes me every time I play that such tastes are subjective. Some people love Dominion, others tire of it quickly.

One player gets up and does something else when it's other players' turns, another two players change their goal from winning to simply messing with other players to the point of annoyance, ruining the game for them.

In fact, I think I've only come across one person who loved to play Dominion the way I do, and that's the man who introduced me to it!

Finding friends (or even strangers) who enjoy any game as much as I do is a rare find. Consider a tabletop RPG: some players get into the game so much they're acting as their character and practically LARPing, while others find that a distraction and prefer to abstract the game into pure mechanics. Still others dislike such games altogether, and too many people refuse to try such a game, either because it's too complex or too nerdy for them.

This applies just as much to videogames, in fact. Playing games online with strangers often results in meeting a lot of jerks that ruin the experience with their behavior. Other times, trying to find even a single friend to play a game in the same room with can be a hassle. At least with online play, you're not restricted to your geographic area.

For me, the perfect people to play a game with are those that are in the same room as me, and are into a game with about the same level of enthusiasm as me. In my own life, those friends are rare. I envy those that have such friends.

And so it strikes me that I find comfort in single-player games, because it's just me and the machine. It's unlikely that a single-player videogame will have enemies that cheat or are obnoxious.

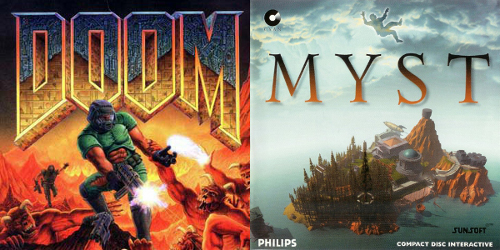

I grew up that way, for the most part. My Nintendo was usually played without a second controller plugged in, and whenever I tried online play on my PC, I could never get DOOM or Warcraft to connect right (old crackling modems that tie up the phone line were a primary source of frustration for me in those days).

It wasn't until I moved to a new neighborhood that I met someone that enjoyed videogames, and we typically played fighting games like Tekken and Mortal Kombat, or other competitive games like Twisted Metal, Smuggler's Run, etc. About the only time we cooperated was when we played single-player games, where we'd trade off or consulted each other with games like Ace Combat 4 and Starflight.

But that friend lost interest in videogames, and it wasn't until college that I met a friend who broke open tabletop games for me, and got me into Dominion and Cosmic Encounter. Now, after college and being back home, the lack of people who enjoy videogames gets to me.

So it's back to single-player games again.

I've stopped to consider an interesting idea about single-player games: they are rare on the tabletop. Sure, there have always been timewasters like Solitaire, but there are rarely (I have not seen any) single-player experiences like you would find in a videogame. You can't play D&D by yourself, but you can certainly play Final Fantasy alone (indeed, most games in the franchise are entirely single-player).

There is hardly a precedent in sports, either, because even potentially single-player sports like Bowling and Golf are still social activities. You could bowl to get a 300, but more often than not that's a secondary goal to beating the other players in your lane. And when it's not -- even when there is no competition and you're just out to have a good time -- you still go with friends and buy a beer and socialize.

Before videogames, single-player games got boring quickly -- how many times can you play Solitaire in a row? How many crossword puzzles can you do?

I find it pretty fascinating that their are no large-scale single-player board games. There is the occasional game you could technically play by yourself, that relies on the board being the enemy, like Shadows Over Camelot, but the game is untested as a single-player experience and it may be impossible to win alone.

|

| I'm amazed they are a daily newspaper feature. |

Even though the online scene in videogames in growing, there will probably always be a market for single-player storytelling experiences. So I wonder if there is a market for single-player story-driven board games. Perhaps they would have to be designed for both multiplayer and single-player as a first stop.

Such a game would require a new paradigm in thinking. A launching point could be cooperative games that are expanded to allow single-player experiences.

However, one of the major implicit selling points of board games in general is that they're social experiences. You are always two feet away from the next player. You might talk about other things as you play, or all enter the magic circle together and fantasize that the board is a world.

Without the social element, would single-player board games sell? Well, if single-player videogames sell, and other single-viewer experiences, like books, sell, then there is no reason to think not, except that it is unprecedented and the very idea causes a kneejerk reaction that prevents such games from selling.

I wonder if a single-player tabletop game is even feasible, and if so, if it's sellable. Could a person derive enough satisfaction from a story-driven single-player tabletop game that they'd want to buy an expansion? Would they like their experience so much they'd want to tell their friends all about it? Could such a game have enough variety that a player would want to play it again and again and make different choices, changing the story or the experience entirely? Could such a game be created that allows both single- and multiplayer experiences?